Intel's blog post offers a rundown of all the investments that the company has made in extending and improving the x86 instruction set, with features such as SSE, AVX, TSX transactional memory, and SGX secure enclaves acting as a demonstration of how the company has transformed this ancient instruction set into something cutting edge and forward-looking. But the second part of the post takes a more sour note: Intel notes that many of these developments are patented and that it has a history of using patents to protect its x86 innovations AMD, Cyrix, VIA, and Transmeta are all named as victims of this defence.

The post doesn't name any names, but it's not too hard to figure out who it's likely to be aimed at: Microsoft, perhaps with a hint of Qualcomm. Later in the year, companies including Asus, HP, and Lenovo will be releasing Windows laptops using Qualcomm's Snapdragon 835 processor. This is not the first time that Windows has been released on ARM processors—Microsoft's first attempt to bring Windows to ARM was the ill-fated Windows 8-era Windows RT in 2012—but this time around there's a key difference. Windows RT systems could not run any x86 applications. Windows 10 for ARM machines, however, will include a software-based x86 emulator that will provide compatibility with most or all 32-bit x86 applications.

This compatibility makes these ARM-based machines a threat to Intel in a way that Windows RT never was; if WinARM can run Wintel software but still offer lower prices, better battery life, lower weight, or similar, Intel's dominance of the laptop space is no longer assured. The implication of Intel's post is that the chip giant isn't just going to be relying on technology to secure its position in this space, but the legal system, too.

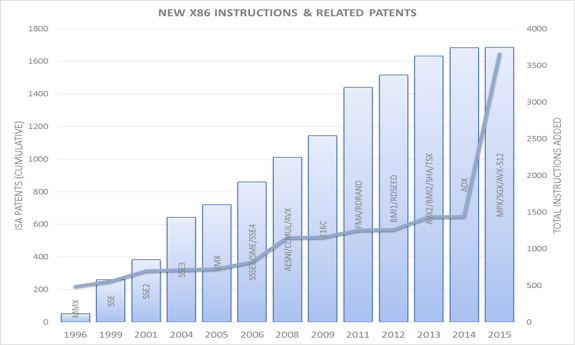

The full details of Windows 10's x86 emulation are unknown; critical to Intel's patent threat will be questions of precisely which x86 extensions are supported. The core 32-bit x86 instruction set is more than 30 years old (it made its debut with the 386, released all the way back in 1985) and as such it's not going to be patent-encumbered. Microsoft's emulator could also safely ignore the very latest x86 extensions such as TSX, SGX, and MPE because software that uses the extensions is so rare. Some extensions, such as the VT-x virtualization features, are irrelevant to running Windows applications, so they can similarly be skipped.

This leaves the extensions with widespread application adoption that are new enough to still be covered by patents. For the most part, these extensions all fall into the same category: they're the various SIMD (single instruction, multiple data) instructions that have widespread use in certain kinds of number crunching, video and image processing, and gaming, among other fields. The newest of these instructions, the AVX family, is probably recent enough that developers do not blindly assume that AVX is available. Rather, they will include both AVX code and equivalent non-AVX code so that if AVX is not available, they can fall back to slower but equivalent routines.

But AVX's older predecessor, the SSE family, is much less likely to have such fallbacks. AVX needs fallbacks because developers can still reasonably expect that their programs will be run on machines that don't support AVX, but that's not the case for SSE: AMD made SSE2 a mandatory part of its 64-bit AMD64 extension, which means that virtually every chip that's been sold over the last decade or more will include SSE2 support. As such, developers don't need to bother including a non-SSE2 fallback path just in case SSE2 isn't present. Instead, their software will simply break.

That's a problem, because the SSE family is also new enough—the various SSE extensions were introduced between 1999 and 2007—that any patents covering it will still be in force. If Intel has patents on the SSE family that are applicable to a software emulator (and not merely to hardware clones), it's hard to see how the Windows emulator will be able to avoid these patents while also offering sufficient compatibility with x86 applications.

Of course, this may just be tough talk from Intel, and until the software actually ships, it's hard to know precisely what exposure the emulator has. That x86 is patented is also widely known, so it would be a little surprising if Microsoft had not considered patent liability when developing the emulator. And Intel's business health continues to have a strong dependence on Microsoft's business, which has to make the chip firm a little wary of taking the software company (or its customers) to court.